Photo by Matthew Murphy

Review by Melanie Stangl

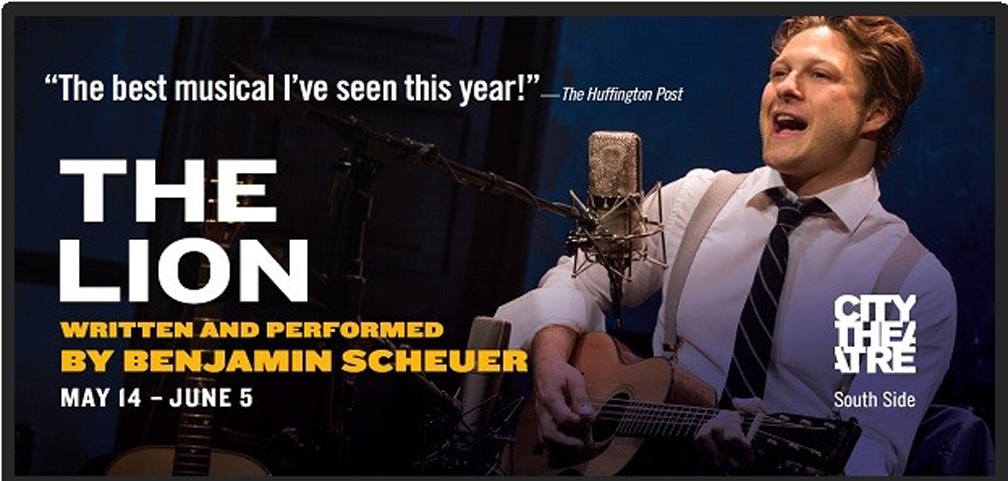

It’s 2 PM on a Saturday, and Benjamin Scheuer has just concluded his Songwriting Master Class in the Hamburg Studio Theatre on the South Side. After this workshop—in which five original songs, submitted by attendees, were performed, dissected, and discussed—Scheuer remains behind, talking to stragglers. I approach him once he’s done chatting about performance opportunities with Sloane, a cheery, precocious 11-year-old. A New York City native, I ask him what his favorite thing about Pittsburgh is—he’s been performing his one-man show, The Lion, at City Theatre’s Main Stage since May 14th. His first reply is somewhat expected: “Meeting songwriters, and going to open mic nights.” He pauses a moment to think, and then adds, “The sound of the trains, too.” I’m surprised. Their sometimes-deafening roar strikes me as more of an annoyance than anything else. But, as I’m to find out when I attend a showing of The Lion later that day, Scheuer’s whole life has been a series of surprises: some great, many terrible. It’s his ability to translate them into song, and to weave a compelling narrative with peaks and valleys both emotional and musical, that makes his one-man, autobiographical show resonate with so many, and that has propelled The Lion to nationwide and overseas tours.

Fast-forward to 5:30. The Main Stage is packed to capacity—a full house, mostly older adults. Before us lies a sparsely-set stage: four microphones, three chairs, and six guitars. Two of them are miniature, child-sized, and one is electric. The wooden flooring, along with a door set into the back wall and a book-stuffed end table, gives the performance space a homey, lived-in feel, which complements the personal nature of the show, in which Scheuer’s familial relationships are a key topic.

The house lights dim and Scheuer steps through the door, sporting a light blue suit and an affable grin, and carrying a seventh guitar. He sits in the center stage chair and begins to play. For the next seventy minutes, the audience is transfixed as we travel along the past two decades of Scheuer’s life: mostly through his singing and playing, with interludes of talking to transition us from one event or era to the next. It begins heartwarmingly enough as he describes how his father, Rick, a mathematician by trade, introduced him to music as a boy with a toy “cookie-tin banjo.” It then moves along to his ten-year-old dreams of starting a band with his father and two younger brothers, with liberal comparisons to the Beatles throughout.

The unvarnished enthusiasm Scheuer shows in that second song highlights one of his primary strengths as a songwriter and storyteller: the ability to speak honestly, earnestly, and believably from multiple points of view. One-man shows run the risk of being self-serving, but The Lion expertly avoids this. He juggles not just his feelings and perceptions from various points in his life, but those of his loved ones as well: his mother, father, and long-term girlfriend Julia all get to air their perspectives. At one point, even his personified illness has a chance to talk. These switches in the speaker of the song happen, for the most part, later in the show, reflecting Scheuer’s growth from the selfish children and teenagers we all tend to be to an adult who recognizes the existence and validity of stories other than his own.

Even when he is speaking from his own viewpoint, he captures the essence of whatever age he is at the time, able to poke fun at himself with 20/20 hindsight while not diminishing the legitimacy of those experiences. After another feel-good tune in which the father asks, “What makes a lion a lion?” and describes his boys as cubs, things take a turn for the worse: we see that Scheuer’s father has a bad temper. He breaks toys, drinking glasses, and eventually his eldest son’s dreams of going to a concert with his school band in D.C. after receiving a poor grade in mathematics: “I guess the stupid kids aren’t going.” A self-confessed “very dramatic fourteen-year-old” at the time (but who wasn’t?), Scheuer leaves a note taped to his parents’ bedroom door, and refuses to speak to his father at all.

Their musical and conversational bonds are severed, but those between the father and Scheuer’s brothers are not. Another pretty, hopeful song from Rick’s perspective demonstrates this, asserting the importance of “the courage we show facing things we don’t know” and “…the way that we weather the storm.” But then, an abrupt change: Rick suffers a seizure, an ambulance is called, he’s admitted to the hospital, his condition is critical. When Scheuer travels to that band concert, he returns to find out that his father has passed while he was gone. The lights dim, his voice cracks. He sings, “Damn you for dying while we were in a fight.

More dramatic upheavals follow: his mother moves the family to her native London and ships Ben to boarding school. There he receives a book of essays from his father’s colleagues, singing his praises, commending his “gentleness” and kind nature. This narrative, so different from the ill-tempered and condescending reality Scheuer remembers, drives him to rebellious anger—and his electric guitar.

This moment in the show highlights another of its key strengths: the ability to adeptly tell his story on musical, lyrical, and visual levels, which makes for a multiplied impact. The switch to electric indicates his adolescent break from the acoustic folk style on which he was raised. His ode to frustration of his father being portrayed as “good St. Rick” begins under a blue spotlight, which transitions to an angry red during the bridge, where in all his teenage certainty, he proposes, “Maybe I’m the only one who knew him.” Scheuer intertwines humor into these intense moments too, relaying a story about his first maths (he emphasizes the “s”—this is England, after all) exam in which he essentially told the grader to screw off, and punctuates the telling-off he received for it with sharp, heated strums.

These ups and downs continue as the show progresses: he moves back to New York, he plays “seriously huge awesome rock songs,” he meets Julia, he falls in love, he begins making peace with his mixed guilt and anger towards his father, his mother is repeatedly distant and unsupportive. Scheuer’s voice, too, displays impressive range: from gritty, powerful, and triumphant in one song, to loving, soft, and wistful in another.

His ability to deliver an emotionally charged, compelling narrative reaches its apex when two devastating blows happen in seeming succession. First, Julia leaves him to travel the world and find herself, in an “invisible city.” Scheuer sings from her perspective, and the last line is particularly moving. Describing her eventual return, she says, “Then you’ll really see me, and I won’t feel so invisible at all.” Second, physical ailments that culminate in a fall at Grand Central Station turn out to be the worst thing possible: cancer. The song that follows details its physical agony and the procedures to counter it; and again, this feeling is portrayed on multiple levels. Scheuer’s voice ascends into a high, unsettling, scratchy falsetto that reflects the scariness and unreality of his situation, accompanied by frenzied strumming interludes. The lights gradually dim as the song progresses, until one tiny light on the floor of the stage is all that remains, leaving his pained face half in shadow.

What happens next? You’ll have to find out for yourself: The Lion runs until June 5th. But rest assured, the coming-of-age themes presented here are accessible without feeling stale, moving without feeling cheesy, deeply personal without feeling alien. Scheuer displays the potential of music as catharsis, as storytelling, as a means of connection, and as a way to confront (or hide from) your demons. He sprinkles just the right amount of genuine humor and heart throughout to balance out the heavier moments, tied together with clever songwriting and clear musical skill.

I still don’t know exactly why Ben is so fond the recurring sound of Pittsburgh’s trains. Maybe it has something to do with their enormous, unapologetic presence, or the way they harken back to earlier, simpler times.

Or maybe…it’s the way they roar.

Master Class photos by Melanie Stangl